At Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

#notebook

Warning: big spoilers. Don’t read on if you intend to play the game.

-

Many of the environmental puzzles (the trees with apples, the shadows thrown by the branches, the bird song) feel trite in comparison to the symbol-based puzzles. Each has a single idea, whereas the symbols build into more complex, interesting structures.

-

The puzzles that rely on the interaction of symbols succeed in a way that feels similar to Braid. Each element is simple, but their combination produces an interesting complexity.

-

I played the game with my wife, Lauren. We switched off on the controller, and spent most of our time talking things through. It was strange to play the game this way because we had to communicate our thoughts about non-verbal things. A lot of our communication ended up being gestural, rather than verbal.

-

Free of the environmental threats that are typical in first-person games, Lauren learnt to navigate a 3D world with the twin sticks on the controller. I wish we’d played this game before playing The Last of Us.

-

Jonathan Blow, the game’s lead creator, advocates that games emphasise the thing that sets them apart from other mediums: interactivity. This makes The Witness a little disappointing. Interactivity isn’t very important in the puzzles. You could input your solutions on paper. Certainly, moving your POV around the world is interactive, but it’s not a new thing.

There’s a wonderful exception that comes late in the game when you solve a set of puzzles on broken monitors that rotate or translate their image depending on the position of your pointer.

-

The puzzles can be very roughly grouped into two categories: environmental and symbolic. The environmental ones require you to reproduce on a puzzle a pattern that is represented in the environment.

These puzzles are mostly uninteresting because the possibilities are unconstrained. Am I supposed to be observing the colors peeking through those slats in the wooden floor? The arrangement of leaves on the ground? The shadows made by the foliage on the trellis? You can find patterns in anything, and the puzzles are mostly a matter of figuring out which pattern has been selected by the game maker to be represented in the puzzle.

The successful environmental puzzles make the relationship between the environment and the puzzle very clear by making the puzzle affect the environment in an obvious way. Then, the constraints are clear. Some examples. The line drawn on a puzzle produces a beam that you have to weave around real objects in the room. A set of puzzles where you have to move your POV around so you can sight puzzles through the right colour of glass to see them clearly. Puzzles where the exit you choose changes something about the world.

-

Part of the goal of The Witness appears to be to demonstrate interesting phenomena about things in the physical world: spatial constraints, light, colour and so on. It’s unfortunate that the player’s exploratory tools are limited to a POV in 3D space and, occasionally, the ability to move a thing on a predefined path.

In a set of puzzles that involve reflection, there are some lights and a body of water. In a set of puzzles about shadows, there is a sun and some branches. The player’s ability to explore the interactions between these elements is limited because the degrees of freedom for these items are severely restricted. The water may be raised or lowered. The sun and branches are fixed. The POV can be rotated, or moved along the ground. As a cognitive media, The Witness is poor. My understanding of the phenomena ended up hazy.

-

Some of the themes in The Witness echo things I’ve felt when I’m programming: the beauty of seeing a connection after learning something new, seeing a concept have relevance elsewhere in my life, the joy of going from not understanding to understanding, the joy of increasing skill. But these sensations in The Witness are poor imitations of the ones I’ve had with programming, because I care a lot about programming but I only care a little about spatial phenomena.

#notebook

Philip Roberts: What the heck is the event loop anyway? | JSConf EU 2014 - YouTube

#notebook

GOTO 2015 • The Secret Assumption of Agile • Fred George - YouTube

#notebook

Margarito d'Arezzo, The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Scenes of the Nativity and the Lives of the Saints

Veronese, The Conversion of Mary Magdalene

#notebook #medianotes

https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2013/10/21/interview-jan-willem-nijman-on-nuclear-thrones-feel/

Nijman: Alright, let’s try this.

When you fire the pistol in Nuclear Throne, first of all the Pistol sound effect plays. Then a little shell is ejected at relatively low speed (2-4 pixels per frame, at 30fps and a 320×240 resolution) in the direction where you’re aiming + 100-150 degrees offset. The bullet flies out at 16 pixels per frame, with a 0-4 degree offset to either direction.

We then kick the camera back 6 pixels from where you are aiming, and “add 4 to the screenshake”. The screenshake degenerates quickly, the total being the amount of pixels the screen can shake up, down, left or right.

Weapon kick is then set to 2, which makes the gun sprite move back just a little bit after which it super quickly slides back into place. A really cool thing we do with that is when a shotgun reloads, (which is when the shell pops out) we add some reverse weapon kick. This makes it look as if the character is reloading manually.

The bullet is circular the first frame, after that it’s more of a bullet shape. This is a simple way to pretend we have muzzle flashes.

So now we have this projectile flying. It could either hit a wall, a prop or an enemy. The props are there to add some permanence to the battles. We’d rather have a loose bullet flying and hitting a cactus (to show you that there has been a battle there) than for it to hit a wall. Filling the levels with cacti might be weird though.

If the bullet hits something it creates a bullet hit effect and plays a nice impact sound.

Hitting an enemy also creates that hit effect, plays that enemies own specific impact sounds (which is a mix of a material – meat, plant, rock or metal – getting hit and that characters own hit sound), adds some motion to the enemy in the bullet’s direction (3 pixels per frame) and triggers their ‘get hit’ animation. The get hit animation always starts with a frame white, then two frames of the character looking hit with big eyes. The game also freezes for about 10-20 milliseconds whenever you hit something.

This is just the basic shooting. So much more systems come in to play here. Enemies dying send out flying corpses that can damage other enemies, radiation flies out at just the right satisfying speed, etc. We could keep going on and on. It’s that attention to details and the relationships of all those systems that matter. You might miss an enemy and hit a radiation canister, forcing you to run into danger to grab all that exp before it expires, etc. It’s the mix of things that matters, not the things themselves. I guess what our games have is our view on what makes those values feel and play good. That’s the Vlambeer “feel”.

I’m enjoying this game as much as I enjoyed Spelunky, which is saying a lot.

#notebook

IGDA San Francisco Jonathan Blow 2016 - YouTube

There’s been an interesting arc in game design. People didn’t use to think about mechanics at all. There were a few people who thought like that but most people thought, “Oh I’m doing cool… games” Eventually you got some thinkers at places like the Game Developers Conference that started specifying the parts of design, and mechanics is one of them. And that’s good because it spread awareness that’s a thing you could think about.

But I don’t think about things in terms of mechanics really at all, because it becomes limiting. Because, really, you want to make a thing that’s integrated. Like, what colour a tree is in The Witness is a game mechanic for several reasons. Forgot all the spoilery reasons, but just like how much attention does it grab when you walk into an area determines how that area is played, and how how puzzle that’s completely unrelated to that tree might work people may have a prominent thing in the back of their mind while they’re trying to do it. That’s a game mechanic, but most people would tell you it’s an aesthetic. At some point, those distinctions don’t matter. At some level of refinement of the craft, they go away.

However, when you’re learning and someone’s trying to get those concepts across, then maybe those things are important, provided they’re taught with the caveat, “You’ll go beyond these eventually”.

#notebook

http://cognitivemedium.com/emm/emm.html

#notebook

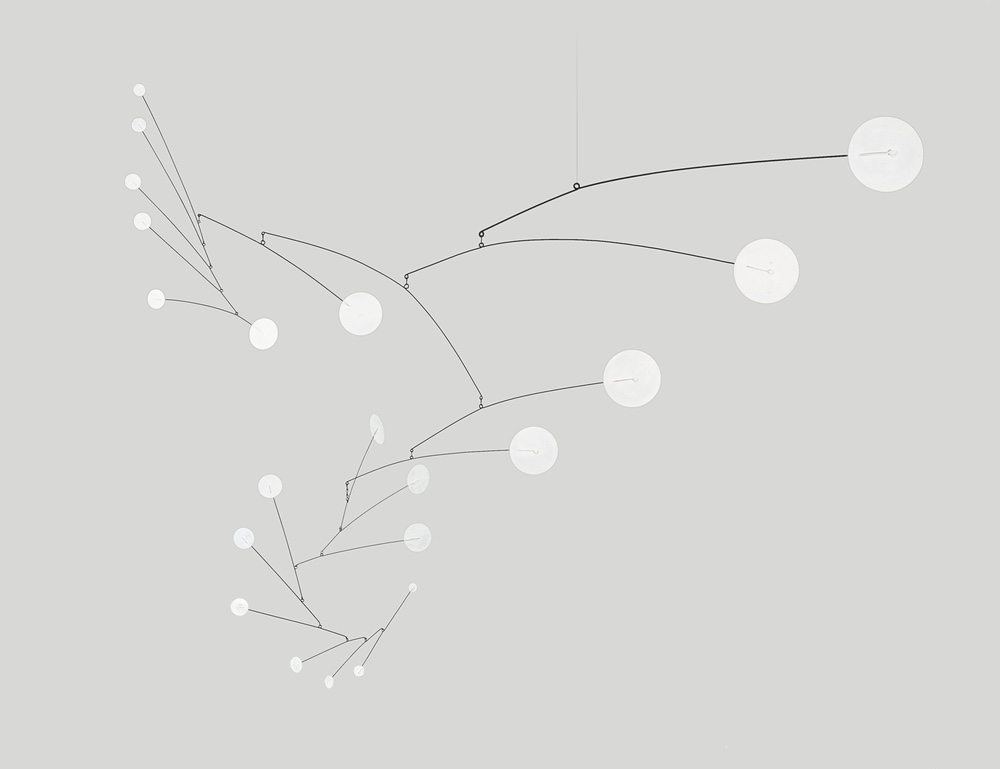

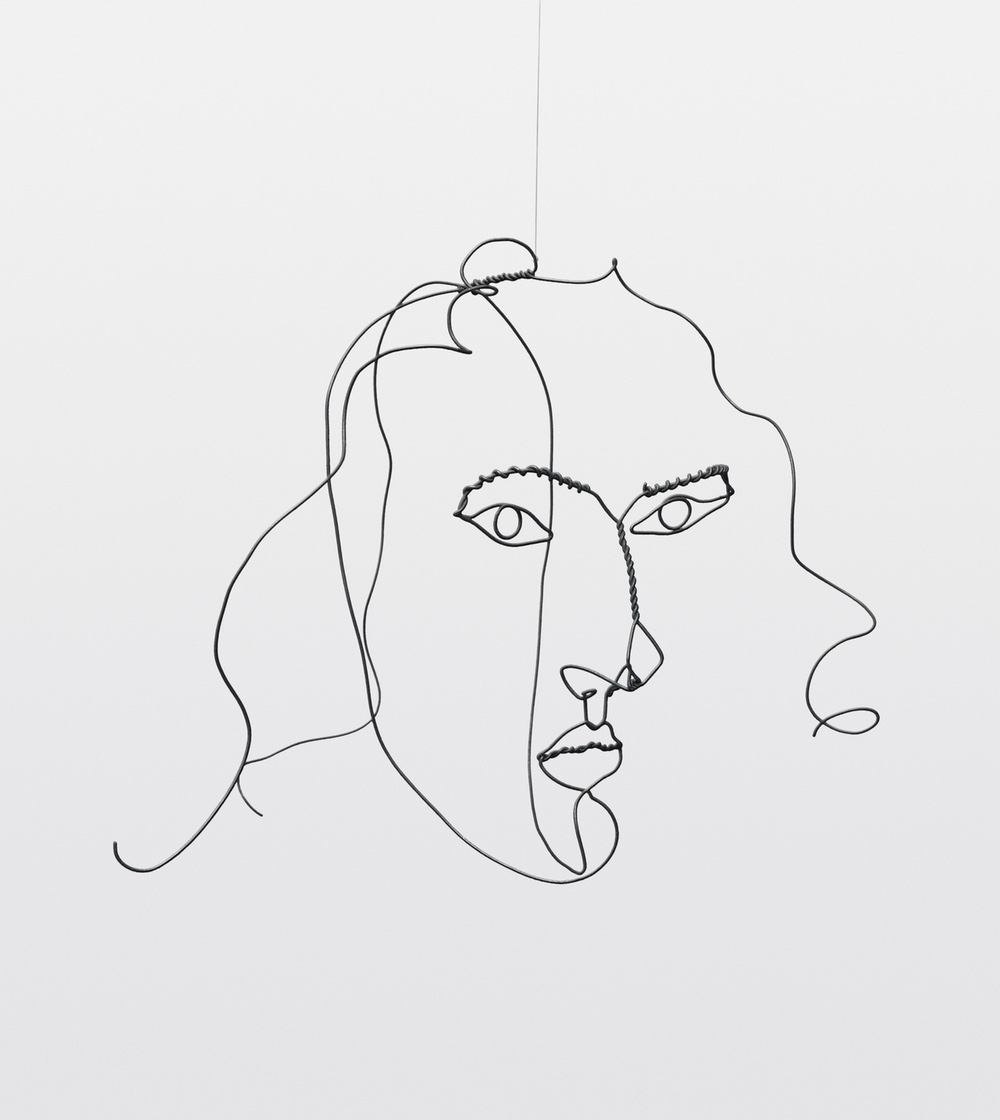

My Dad and I went to the Calder exhibition in London. It’s hopeless to look at pictures. The magic is in your changing aspect on the cascades of lines in Snow Flurry (top) as it goes round, or changing your view through Medusa’s wire head (bottom).

#notebook #medianotes

Slingshot is a super interesting profile of Dean Kamen, the creator of a drug infusion pump, a portable dialysis machine, the Segway, and a machine that makes any water potable.

#notebook #medianotes

They called the process of informal collaboration by the name “Tom Sawyering.” Like Tom with his paintbrush and whitewash, someone would set forth his idea or project—whether it was in a formal meeting or a hallway bull session was unimportant—to mobilize a few intrigued colleagues in an attempt to make it happen. If you saw a glimmer of how to implement a new operation in microcode, you would gather a few expert coders in a room and have at the problem until every whiteboard in the place was filled with boxes and arrows and symbols as arcane as Nordic runes. If you had a big project with a lot of soldering to be done, everyone who knew how to wield a soldering gun strapped on his holster.

If an idea worked, the team stuck together for the next three or six months to complete the job; if not, everyone simply dispersed like free electrons in search of a new creative valence. Thacker viewed this system as “a continuous form of peer review. Projects that were exciting and challenging received something much more important than financial and administrative support. They received help and participation… As a result, quality work flourished, less interesting work tended to wither.”

In this spirit Systems Science Lab engineers wrote code for Computer Science Lab hardware, CSL designers helped SSL build prototypes, and the General Science Lab’s physicists chipped in with valuable insights into material properties and electrical behavior (as when Dave Biegelsen told Starkweather how to use sound waves to modulate a light beam and got his offhand suggestion incorporated into the world’s first laser printer).

At one point Tom Sawyering even begot an audacious extracurricular project. This was the so-called “Bose Conspiracy,” which was hatched at a poker game at Rick Jones’s house. Jones, Kay, Thacker, Dick Shoup, Chuck Geschke, and a couple of others had fallen into a discussion of the merits of stereo speakers. Kay was a particular fan of the state-of-the-art Bose 901s, which came with their own electronic equalizer and cost $ 1,100 the set (in the pre-oil shock dollars of the early 1970s). He was also the only one in the group who owned a pair, having acquired them on his PARC budget as part of a real-time music synthesizer his group was developing.

“You know,” someone said as cards riffled in the background, “there’s no reason why we couldn’t make the electronics work just as well. And for a lot less money, too.”

Appropriating a basement room in Building 34, the group took apart Kay’s speakers and painstakingly analyzed the design. They bought cone speakers from the same Kentucky factory that supplied them to Bose, and on a shrieking diamond-toothed radial saw in Jones’s garage they cut and shaped the sound baffles out of high-density particle board. (The marathon session left Kay covered with an inch-thick coating of sawdust and Jones with a lifelong case of tinnitus.) Then they apportioned the assembly tasks—one conspirator handled the soldering, another installed the speaker cones, and so on—the same way they had distributed the tasks on MAXC, which happened to be running contentedly in its own air-conditioned room a few doors away. All told, they manufactured more than forty pairs at $ 125 each. The buyers among their PARC colleagues could customize the units with their choice of grille cloth but were otherwise challenged to tell the knockoffs apart from the real thing. No one could.

“It was so typical of PARC,” Kay recalled. “If you didn’t know how something was done, you just rolled your own.”

#notebook

It really stuck with me. The natural lighting. The grubbyness and inscrutable faces, occasionally pierced by a humane eyeball.

#notebook #medianotes

Because most actors and actresses are trained in some variant of the Stanislavsky System [1], they have a way of understanding fictional characters that’s not well known to the general public. This is too bad, because it’s a really fun way to think about fiction, one that’s useful to writers and critics as well as actors (and directors), and even if you’re “just” an audience member or reader, it’s still enlightening. I wish it was taught in Literature and Film Studies classes.

In each scene (or in each meaningful part of a scene), a character has a goal, sometimes called his “action.” Actors generally express actions as infinitive verbs, centered on another character, as in “My action is To Seduce her” or “My action is To Convince him to sell the estate.” Though (depending on what happens in the script), a character might not achieve his goal, it must at least be achievable in theory. In other words, the actor has to know what would count as achieving it, so that when he’s acting, he’s striving for something tangible.

Stanislavsky-style acting focuses on active goals (actions) rather than emotions. So if an actor is trying to be sad, his director is likely to ask him to stop doing that and, instead, try to achieve a particular, specific goal.

In light of that, some might say To Seduce is a bad action, because it’s too general. When do you know for sure if you’ve seduced someone? Do they actually have to have sex with you? Do they have to fall in love with you? As a director, I ask actors a lot of questions about their actions, especially when a scene is not going well.

Me: What are you trying to achieve?

Actor: I’m trying To Seduce her?

Me: How will you know if you’ve succeeded?

Actor: …. um … Well, if she smiled at me or something…

Me: That doesn’t seem specific enough. That could equally be the result of the action To Entertain her. I think if we come up with something more specific for you, you’ll have an easier time committing to the scene.

Actor: Okay. I’m trying to get her to touch me.

Me: Just to touch you?

Actor: To kiss me!

Me: Great, so if she kisses you, you win the scene. If she doesn’t kiss you, you lose. Everything you do in this scene is an attempt to get her to kiss you.

And all the things the actor does are tactics employed to achieve his goal. For instance, if his first line is “You sure look pretty, today!” he might think of that as a tactic of flattery, used to achieve his goal of getting a kiss. Tactics can be played using lines (and every line must be some sort of tactic) or physical actions. For instance, when he moves closer to her, that might be a tactic of pursuit, meant to further his goal of getting a kiss.

A scene isn’t a scene without conflict, so presumably she doesn’t want to kiss him, or she does but is scared to. (If she does want to kiss him, has no fear of kissing him, and, in fact, does kiss him in the first minute of the scene, he needs to choose a different action. Your goal can’t be to obtain something you already have.)

So, in an attempt to play her action, which might be To Fight Him Off or something totally unrelated to his action, like To Get Him To Help Her Clean the Kitchen, she throws obstacles at him. Maybe he compliments her, but she shrugs it off (obstacle). He moves closer to her, but she backs away (obstacle). He has to constantly adjust his tactics in light of these obstacles.

He might also throw internal obstacles at himself. For instance, maybe she point-blank asks him, “Why did you come to see me?” Rather than saying, “For a kiss,” maybe he pauses and laughs. He’s thrown by his own shyness (internal obstacle).

An action is over when a character achieves his goal or totally loses it – or, sometimes, because a scene ends. (It might end before the conflict is resolved.) If a character is still “in play” after winning or losing, he’ll have a new action. It’s somewhat rare for a character to switch actions mid scene, but it happens. There’s a striking example (in fact, an amazing example!) in “Titus Andronicus.” See if you can find it. Hint: it happens to the title character.

You can go through a whole play and analyze it this way, giving each character scene goals based on textual evidence. Each time they do or say anything, you can think about what kind of tactic it is (or is it an internal obstacle playing out?). Drama tends to happen when two or more characters have actions that are at odds with one another.

It’s a great meeting of art and “science.” By which I mean there’s creative leeway (not one right answer), but actions, tactics and obstacles can’t just be anything. They must be rooted in the text.

I’ll note that characters aren’t always aware of their actions. From their level, actions might be subconscious. Also, the point isn’t to telegraph your actions to the audience. It’s not a guessing game. (Jack Nicholson once admitted that he was trying to seduce Nurse Ratched in parts of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” This was his secret. He didn’t even want the audience to know. But it made the scenes exciting for him, and the audience had the sense that something really interesting was going on, even if they couldn’t pinpoint it.)

If you enjoy analyzing scenes this way, you can do it with any form of fiction (that’s about characters). Not just plays and movies. And it’s a great way for writers to come up with character motivations. I once heard Ang Lee talk about staging a car chase as if each car was a character with opposing actions.

#notebook

There are several techniques for stimulating lateral thought. One technique we used frequently at Apple was called Random Entry. I worked closely with a designer who leaned on it very heavily. Using this technique, I generated at least a dozen patents.

Here’s how it works: You start with a well-defined problem statement. Then, choose a random word; de Bono provides a table of words that you can traverse by rolling dice multiple times. Then spend the next three minutes coming up as many ideas as possible that associate that word with the problem statement. Discuss the ideas amongst your team, building on them where they stimulate deeper discussion. Then pick a new word and start again. This exercise generates a tremendous number of ideas that you likely would not have thought of if you were not trying to use lateral thinking techniques.

To give you an example, let’s say your problem statement is to come up with a new video editing app for the phone. Now, let’s say you pull the word “bicycle.” Think of some things you can do for editing video that you could tie to the word bicycle.

When I tried this exercise, here are just a few ideas I came up with:

An app that overlays iPhone sensor information over live video

A feature to automatically detect your bike tricks and post them to Vine

A “travel-by-map” montage, that uses known bike routes

An 80’s BMX effect pack for iMovie.

The goal here is to free associate. While brainstorming these ideas, I wasn’t thinking about which ideas were the most practical or feasible. That step comes later in the process. I just wrote down what comes to mind.”

#notebook

The illegitimate daughter of Cosimo I. I find it very touching that her father had her wear a pendant with his image in the portrait.

#notebook #medianotes

Circles Sines and Signals - Introduction

The explanations and, in particular, the visualisations, give me a feeling of the beauty of maths that I’ve never really felt before. A wondrous essay.

#notebook

Dorothy was working with me the other day. I have been trying to get to the bottom of her misunderstanding of numbers so that I might find some solid ground to start building on. I think we may have touched the bottom, but it was a long way down.

On the table I made 2 rows of white rods, 5 in each row. As I made them, I said, "Here are 2 rows, same number of rods in each row.” She agreed. I asked how many rods I had used to make these 2 rows. She said 10. I wrote 10 on a piece of paper beside us and put a check beside it. Then I made 2 rows of 7. She agreed that the rows were equal, and told me, when I asked, that I had used 14 rods to make them. She had to count them, of course. I wrote 14 and put a check beside it.

Then I said, "Now you make some.” She pushed my rows back into the pile, and then brought out some rods, with which she made 2 rows of 6. I asked how many she had used, and she counted up to 12. I wrote this down and put a check beside it. Then I asked her to see if she could make 2 rows with the same number in each row and no rods left over, using 11 rods. She pushed her 10 rods back into the pile, then counted out 11 rods from the pile and tried to make them into 2 equal rows. After a while she said, “It won’t work.” I agreed that it wouldn’t, wrote down 11, and put a big X beside it.

Then I said, "Some numbers work, like 10 and 14, and others don’t, like 11. I’d like you to start with 6, and tell me which numbers work and which ones don’t.” After what we had been doing, these instructions were clear. She counted out 6 rods, which she made into 2 rows of 3. I wrote down 6 and checked it. Then I got my first surprise. Instead of bringing out one more rod to give herself 7, she pushed all of them back into the pile, then counted out 7 rods, and tried to make 2 equal rows out of them. After a while she said, “It won’t work.” I wrote 7, with an X beside it. Then she pushed all the rods back into the pile, counted out 8, made 2 rows of 4, and said “8 works.” Then she pushed them all back, counted out 9, could not make 2 rows, and told me so. And she followed exactly this procedure all the way up to about 14.

Then she made a big step. Having done 14, she brought out another rod to make 15, and merely added that rod to one of the rows, before telling me that 15 would not work. Again she left her rows, this time adding another rod to the short row, before telling me that 16 would work. This more efficient process she continued up into the early 20’ s-about 24, I think. Then, having found that 24 would work, she said, but without using the rods, "25 won’t work.” I wrote it, and she continued thus, with increasing speed and confidence, until we got to about 36. At this point she stopped naming the odd numbers altogether, saying only “36 works, 38 works, 40 works…” and so on up into the 50’ s, where we stopped.

We rested a bit, fooled around with the rods, did a little building with them, and then went on to the next problem. This time I made 3 equal rows, and asked her to find what numbers, beginning with 6, would work for this problem. To my surprise, she could not arrange 6 rods in 3 equal rows, arranging them instead in a 3-2-1 pattern. I helped her out, and she began to work. From the start she moved one step ahead of where she had been on the e-row problem. When I had made 6 rods into 3 rows of 2, and had written that 6 worked, she added a rod to one of the rows, told me that 7 would not work, added a rod to another row, told me that 8 would not work, added a rod to another row, and told me that 9 would work. In this way we worked our way up to about 15 or 18. Here she stopped using the rods, and said,” l9 doesn’t work, 20 doesn’t work, 21 works…“ and so on. When she got up to about 27, she just gave me the numbers that worked–30, 33, 36, and 39.

In the 4-row problem we began with 8 rods. She used the rods to tell me that 9, 10, and Il would not work, and that 12 would. Without the rods, she told me that 13, 14, and 15 would not work, and that 16 would; from there she began counting by fours–20, 24, 28, 32, etc. In the 5-row problem we began with 10 rods, and after using the rods to get to 15 she went on from there counting by fives.

Revised edition commentary:

People to whom I have described this child’s work have found it all but impossible to believe. They could not imagine that even the most wildly unsuccessful student could have so little mathematical insight, or would use such laborious and inefficient methods to solve so simple a problem. The fact remains that this is what the child did. There is no use in we teachers telling ourselves that such children ought to know more, ought to understand better, ought to be able to work more efficiently; the facts are what count. The reason this poor child has learned hardly anything in six years of school is that no one ever began where she was just as the reason she was able to make such extraordinary gains in efficiency and understanding during this session is that, beginning where she was, she was learning genuinely and on her own.

Though I have many reservations today about much of the work I did with my fifth-grade classes, I am still very pleased with this day’s work with Dorothy. I don’t think that she, any more than Ted, was internalizing, taking possession of, making her own, much of what I was showing her. But at least she was having the experience of solving problems that she understood, and knowing from the evidence of her senses that she had solved them. At least she was feeling some of the power of her own mind. The problem, my problem, probably seemed pointless and ridiculous to her, but the solution was hers.

#notebook #medianotes

Out of the dusty labs | The Economist

Technology firms have left the big corporate R&D laboratory behind, shifting the emphasis from research to development. Does it matter?

#notebook

http://miriamposner.com/blog/a-better-way-to-teach-technical-skills-to-a-group/

#notebook

Functional languages are are unnatural to use; but so are knives and forks, diplomatic protocols, double-entry bookkeeping, and a host of other things modern civilization has found useful. Any discipline is unnatural, in that it takes a while to master, and can break down in extreme situations. That is no reason to reject a particular discipline. The important question is whether functional prgramming in unnatural the way Haiku is unnatural or the way Karate is unnatural.

Haiku is a rigid form poetry in which each poem must have precisely three lines and seventeen syllables. As with poetry, writing a purely functional program often gives one a feeling of great aesthetic pleasure. It is often very enlightening to read or write such a program. These are undoubted benefits, but real programmers are more results-oriented and are not interested in laboring over a program that already works.

They will not acccept a language discipline unless it can be used to write program to solve problems the first time – just as Karate is occasionally used to deal with real problems as they present themselves. A person who has learned the discipline of Karate finds it directly applicable even in bar-room brawls where no one else knows Karate. Can the same be said of the functional programmer in today’s computing environments? No.

(Via Dan Luu).

#notebook

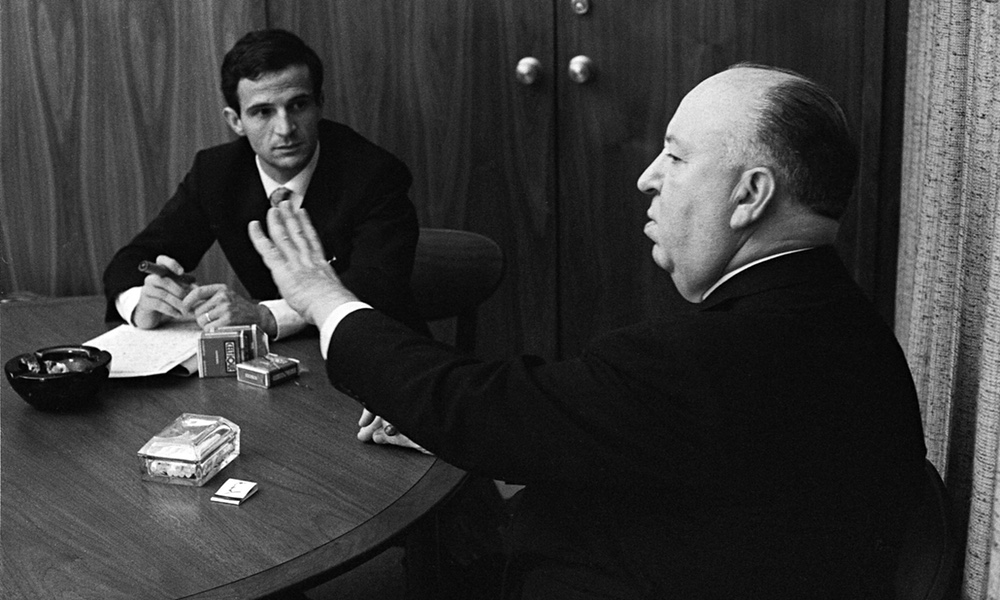

A documentary about a set of interviews that Francois Truffaut did with Alfred Hitchcock. The middle section focuses on a super interesting discussion of film technique.

At one point, Truffaut describes a section of his film, The 400 Blows.

Truffaut describes how the main character is walking with a friend when he sees his mother kissing a man who is not his father. He describes how the mother sees the boy and the boy and the friend hurry away.

In the film clip, the friend says, Who was that? and the boy says he doesn’t know.

Hitchcock says, “I hope you did it without dialogue.”

#notebook #medianotes

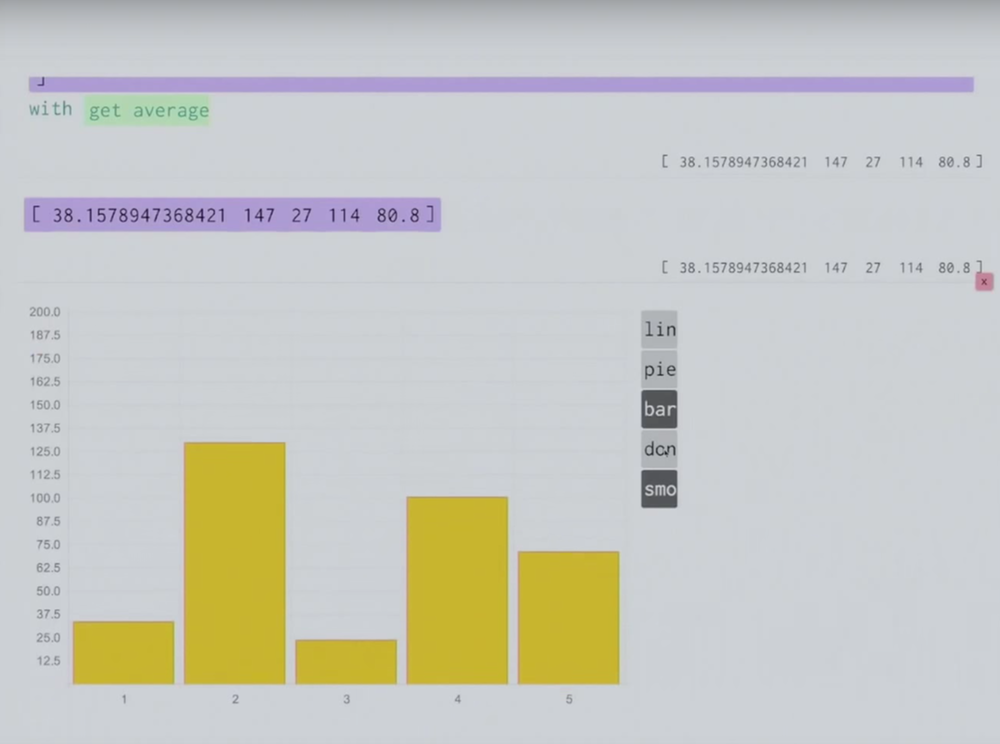

Super interesting description of implementing an emergency JS interpreter.

#notebook

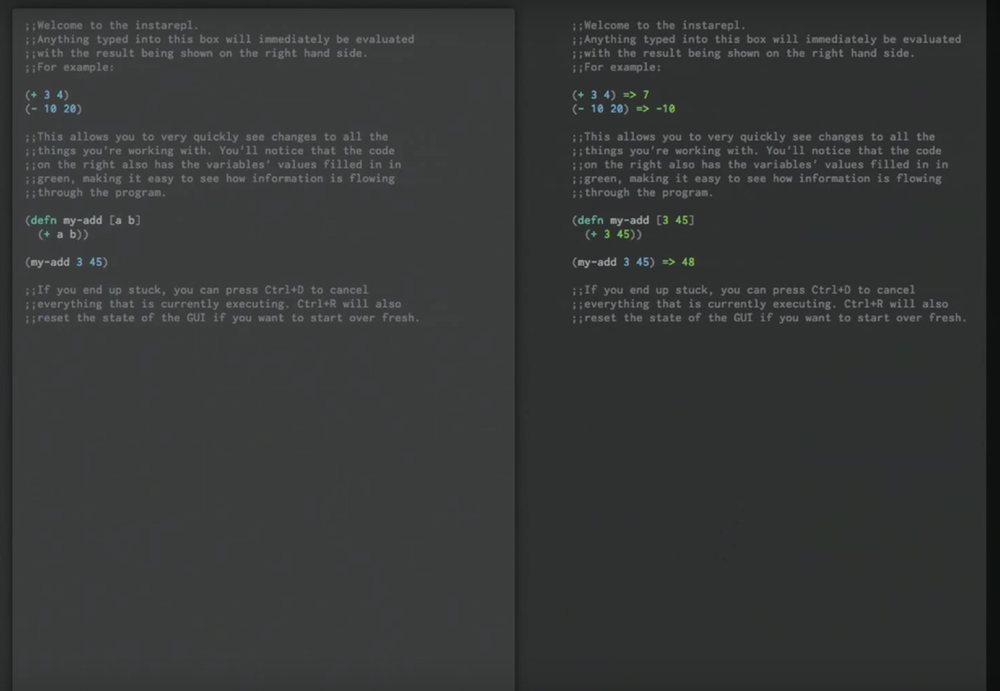

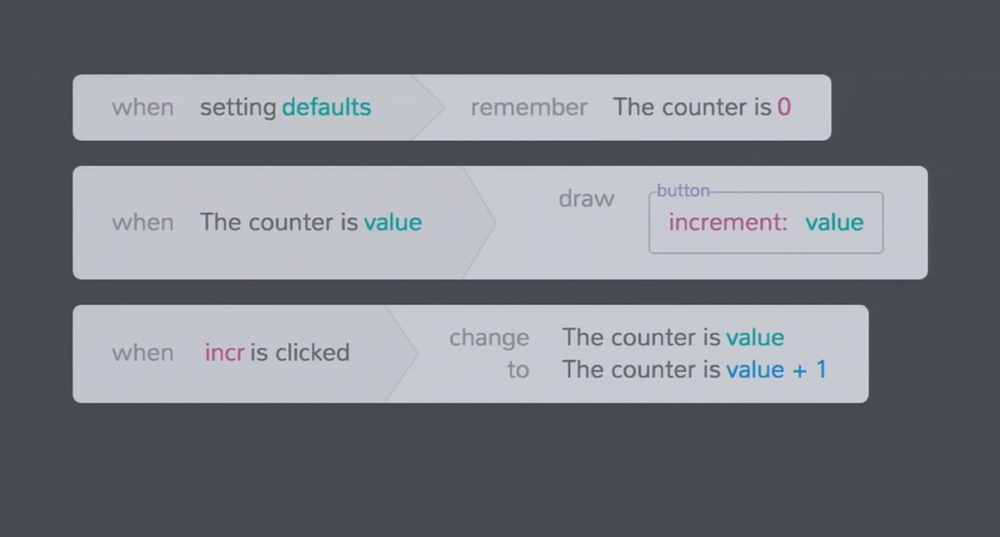

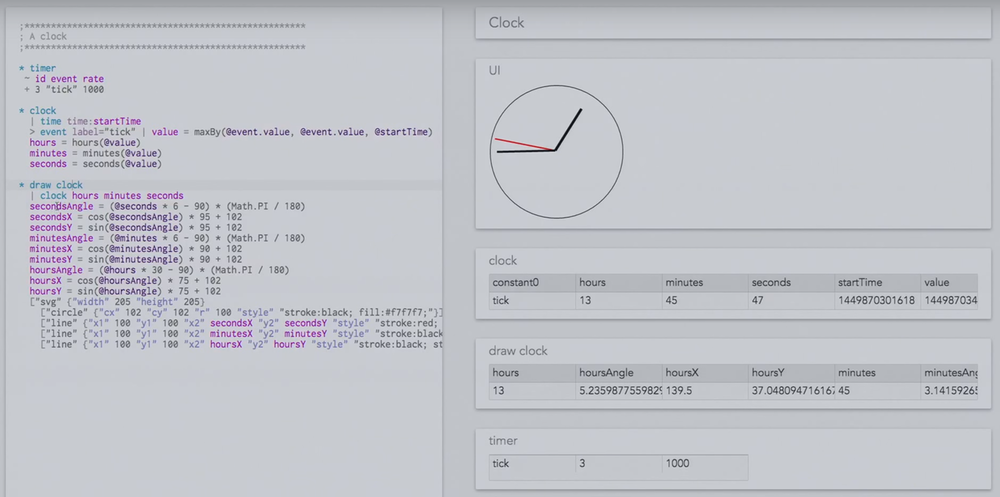

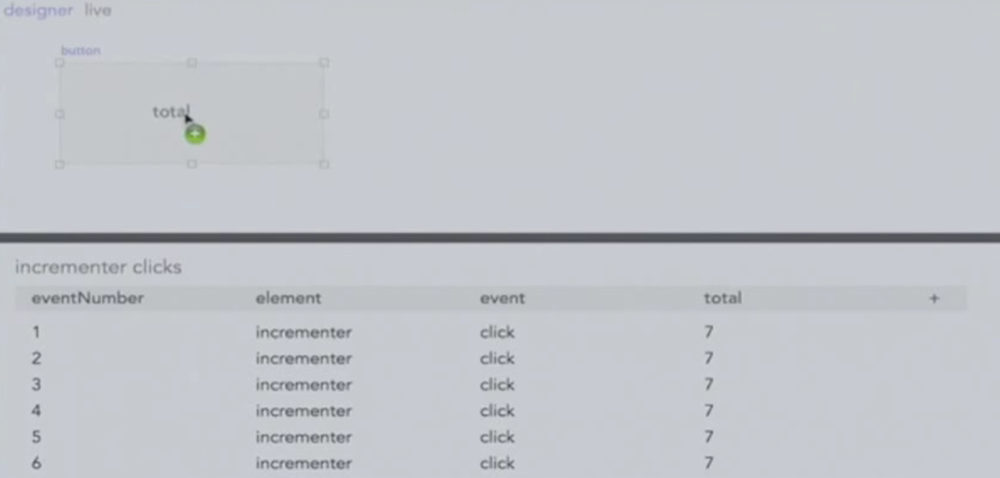

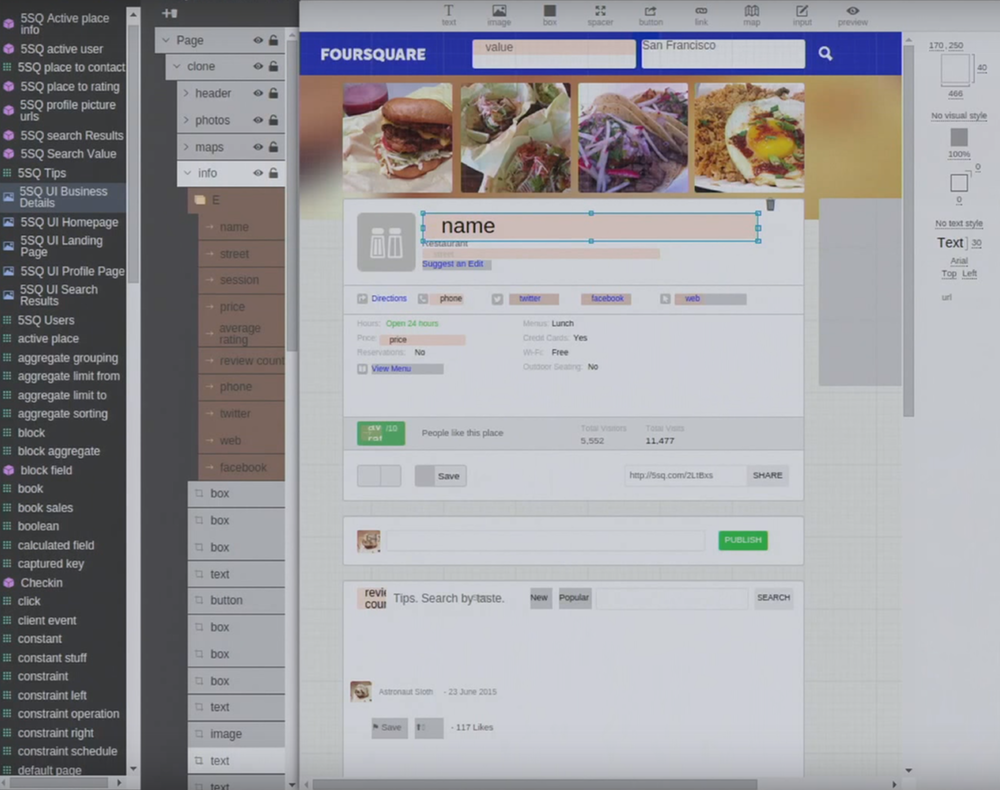

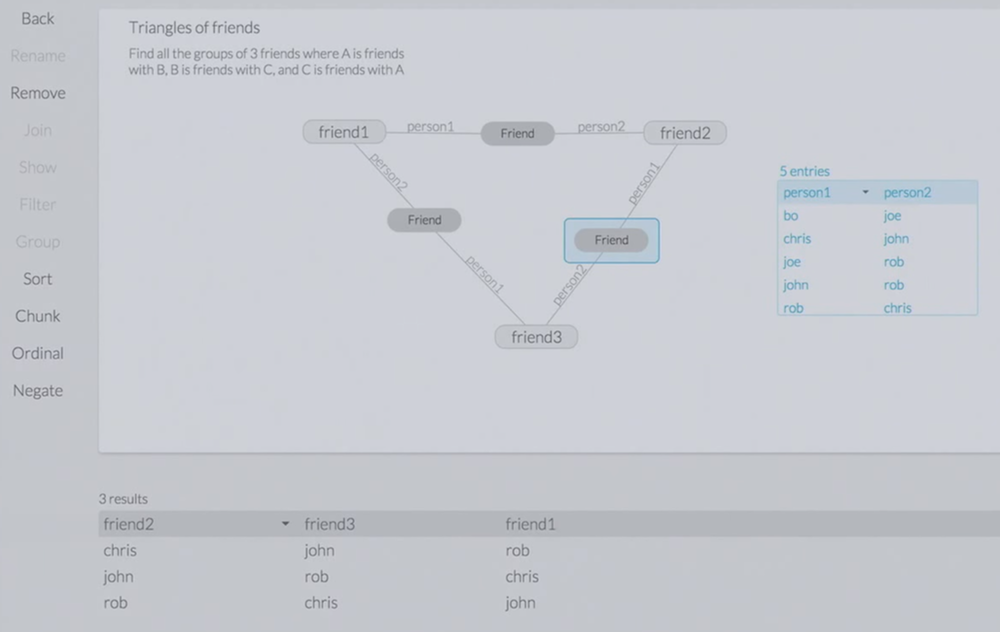

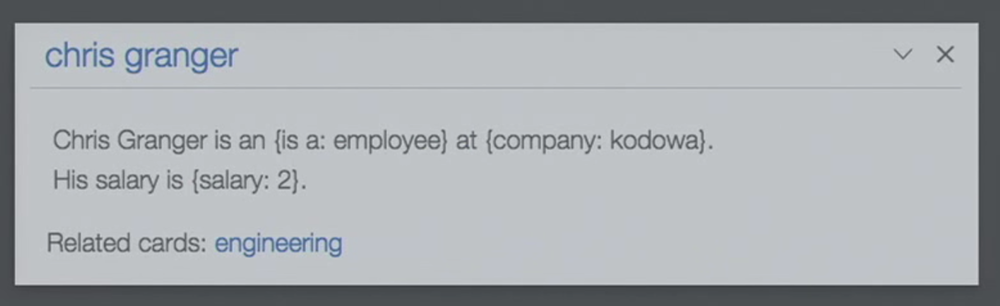

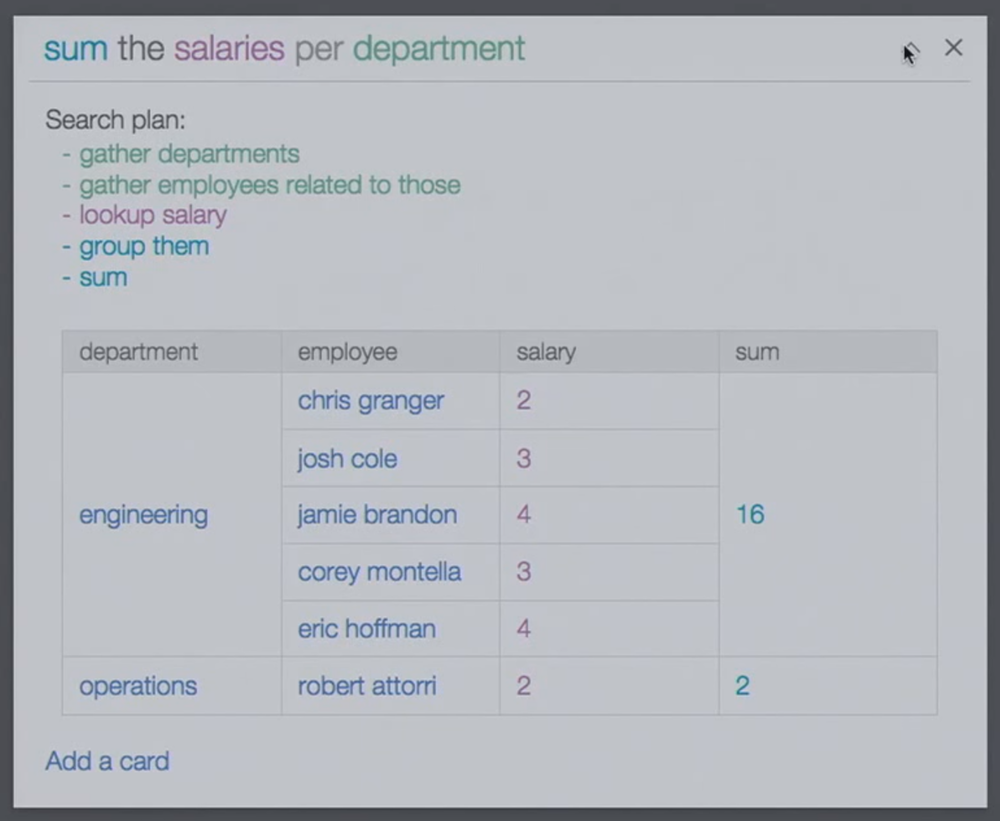

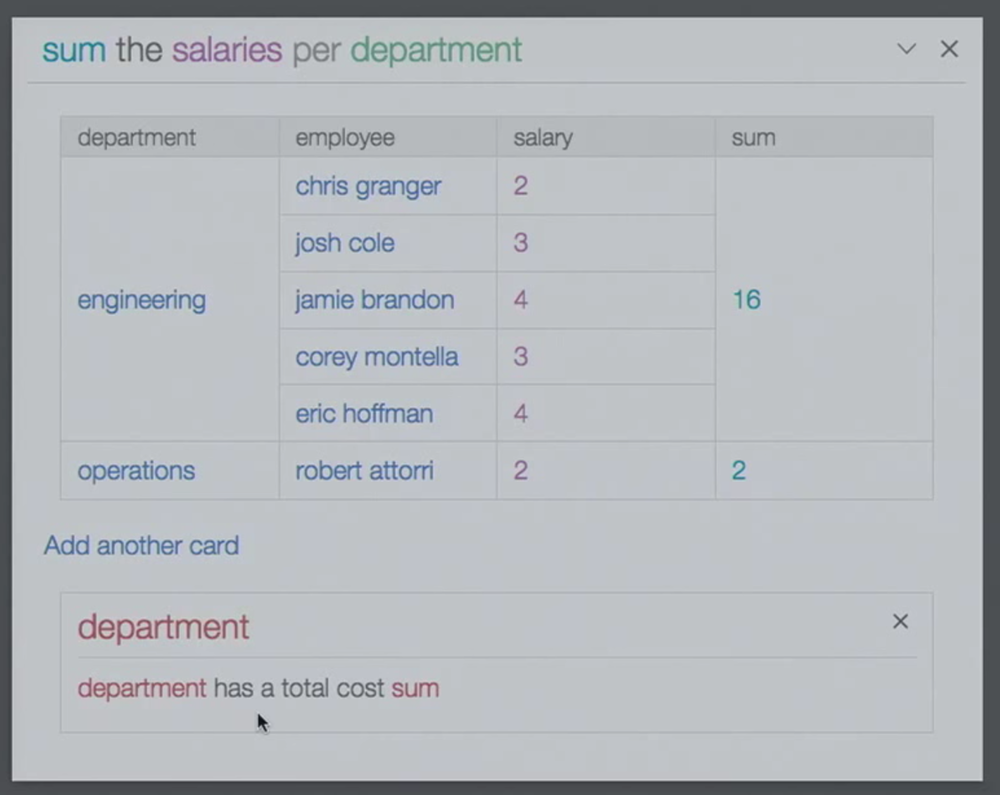

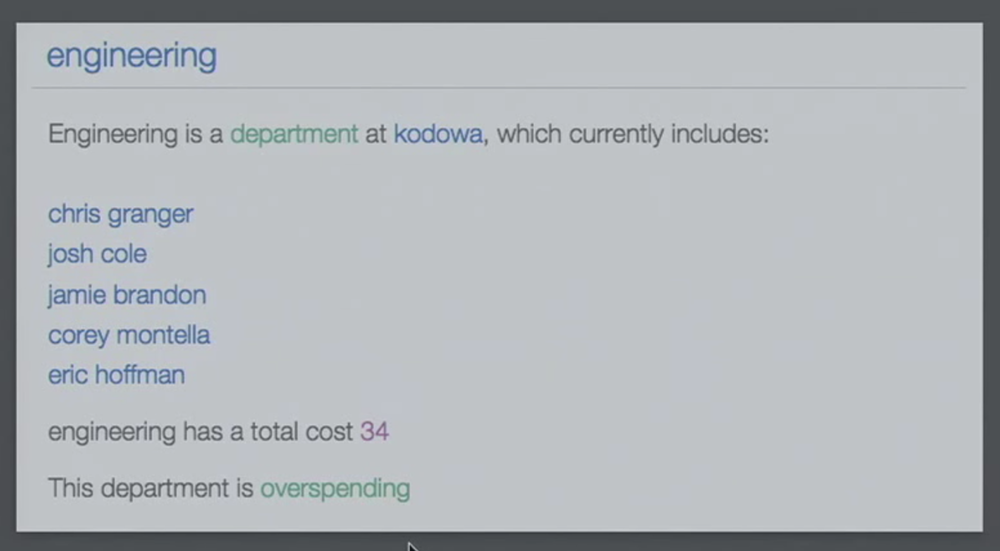

A killer summary of the many prototypes that Kodowa built in search of the future of programming.

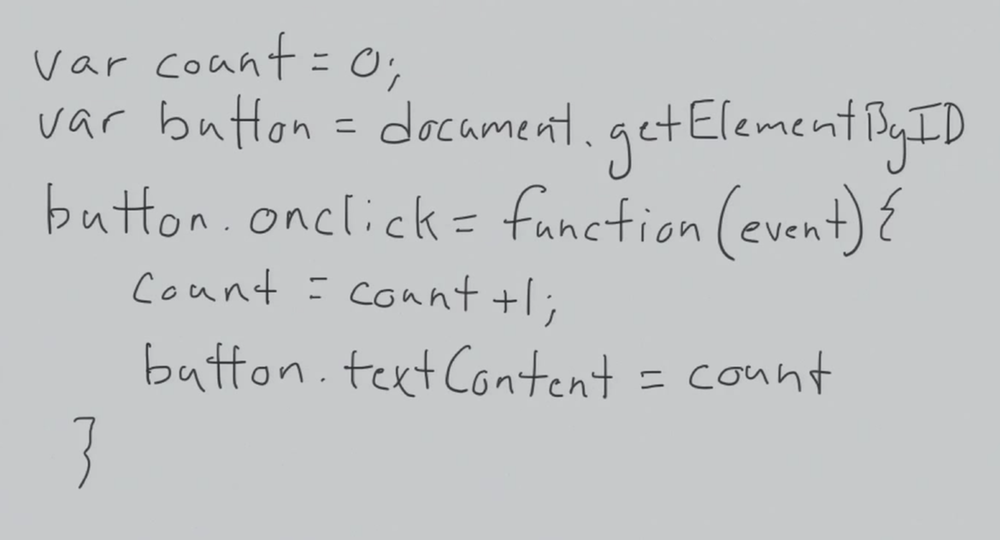

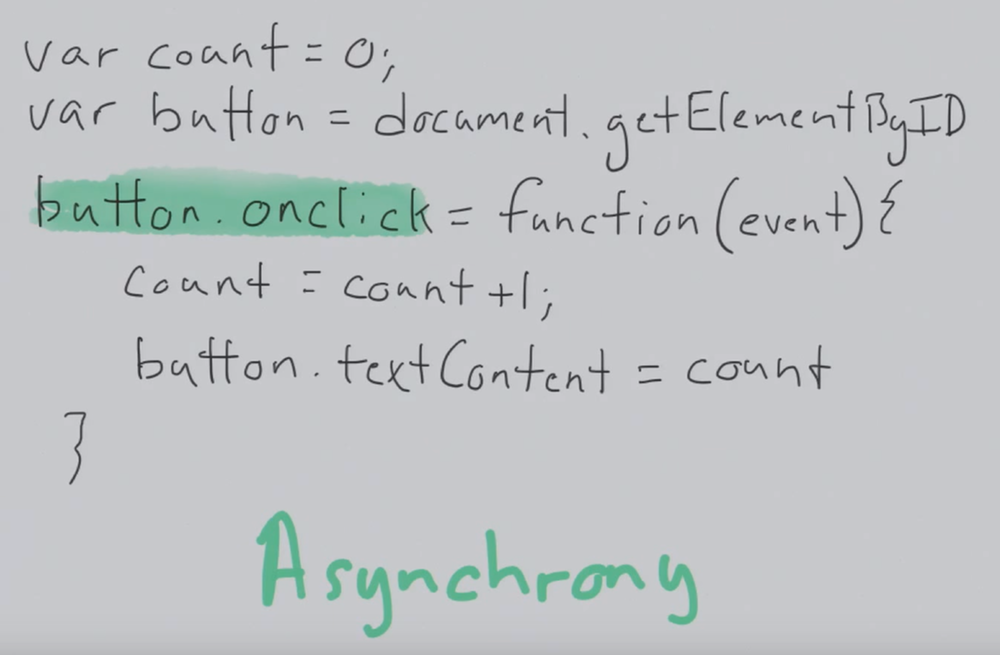

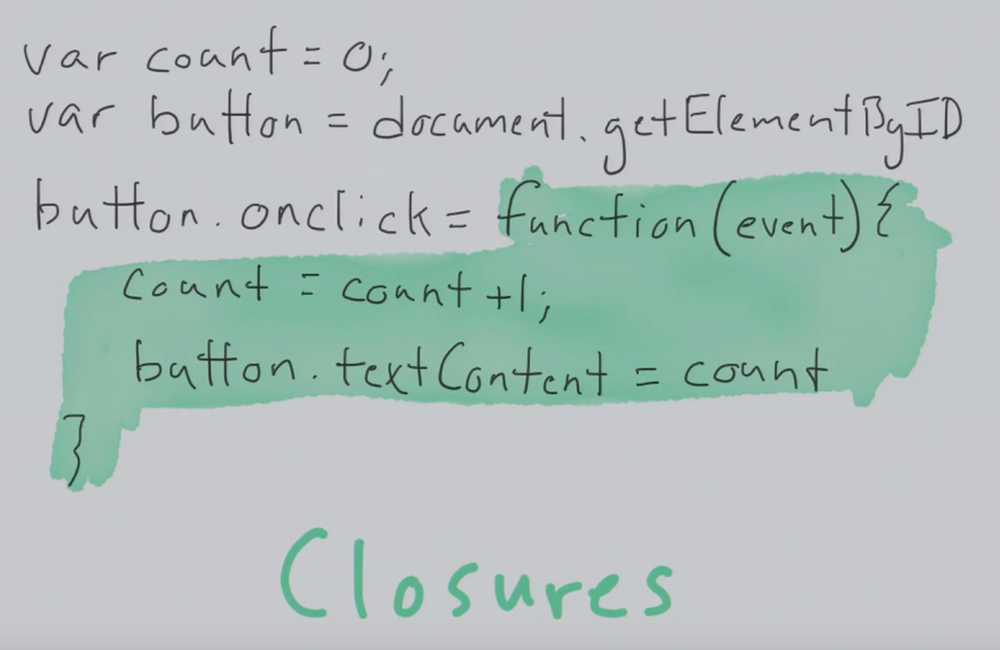

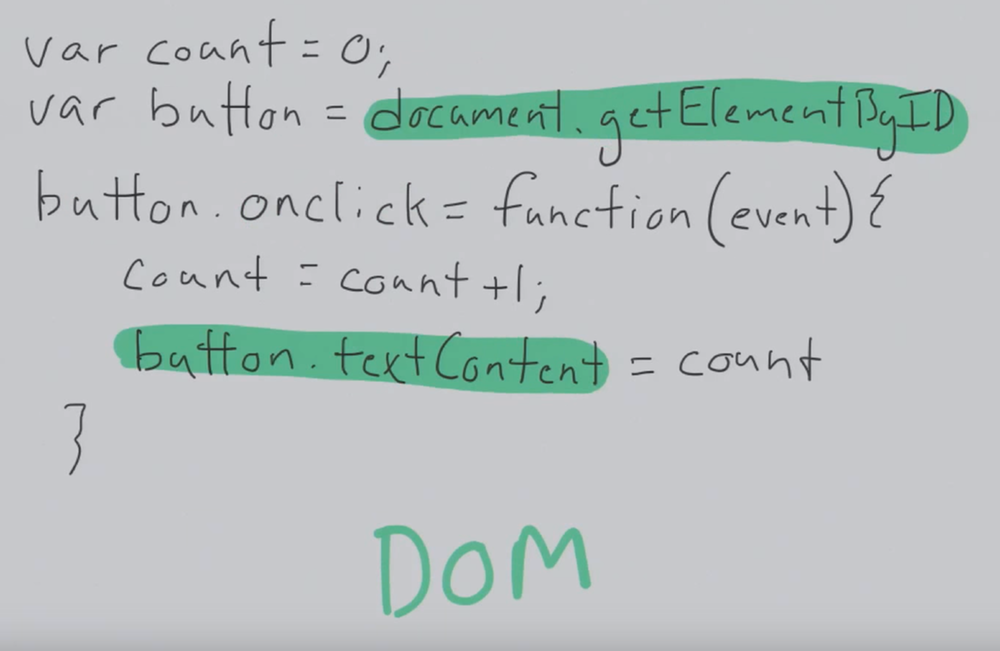

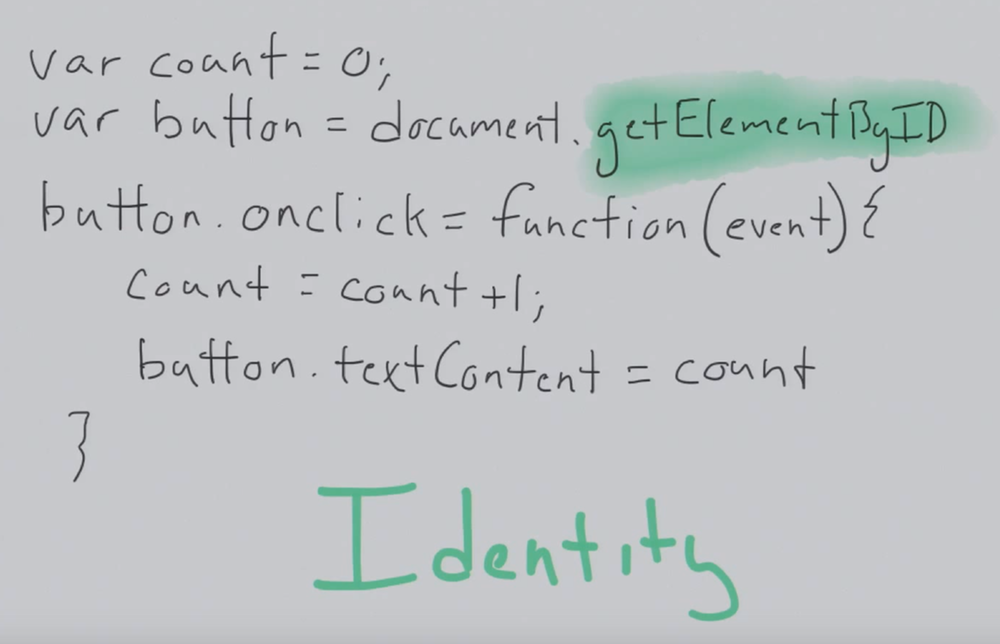

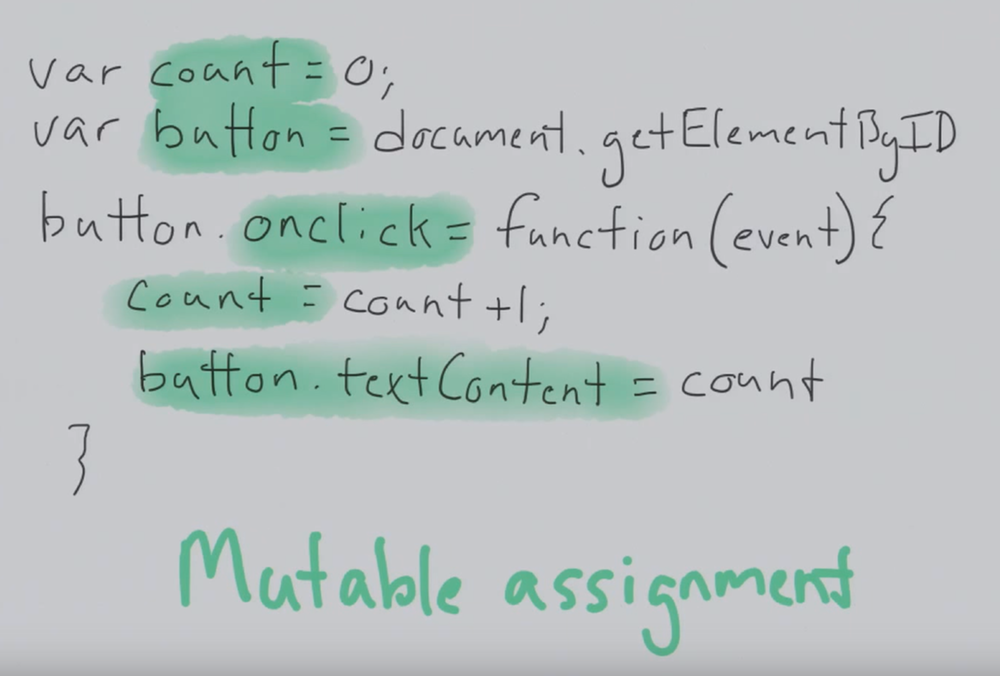

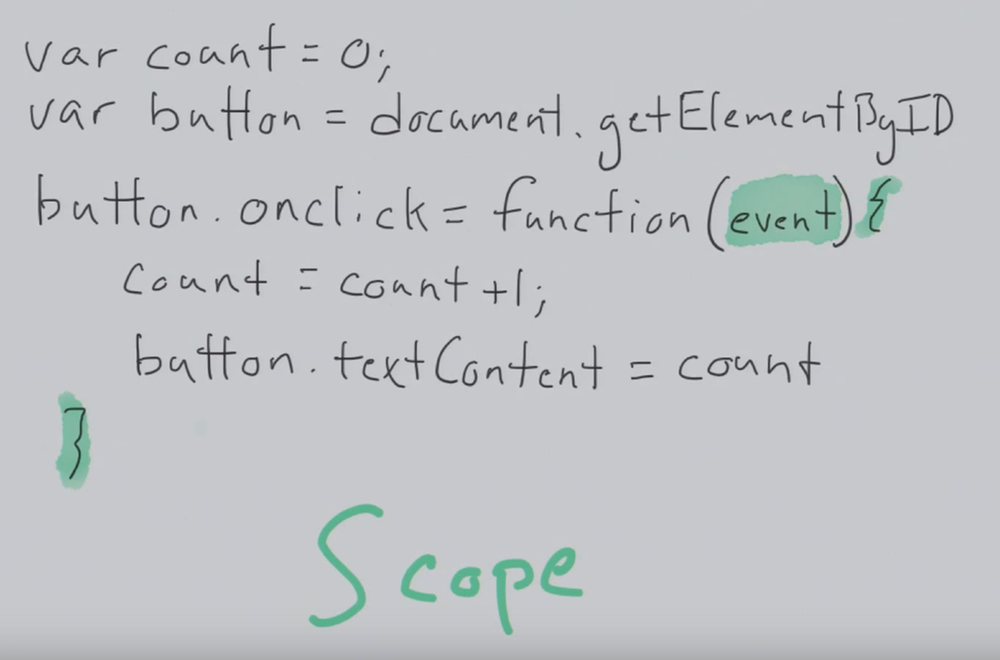

The six lines of JS code required

Asynchrony - incidental complexity

Closures - incidental complexity

The DOM - indirection

Identity - indirection, incidental complexity

Mutable assignment - incidental complexity

Scope - incidental complexity

The user writes wiki-style text documents in a text area. These documents contain tags that specify data and relationships.

The user can query the documents by writing text into a text input field.

The user can turn a query into a card that describes some new piece of information.

This card is shown in relevant contexts.

#notebook #medianotes #build-software-faster

I doubt very much if it is possible to teach anyone to understand anything, that is to say, to see how various parts of it relate to all the other parts, to have a model of the structure in one’s mind. We can give other people names, and lists, but we cannot give them our mental structures; they must build their own.

#notebook

“Well now they knoooooooooooooow…”

Lauren and I sent a video of us singing Let it Go to my niece.

#notebook

Lauren and I visited DC and we spent several hours in the National Gallery. My favourites:

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de Benci

Raphael, The Alba Madonna

Raphael, Bindo Altoviti

Matteo di Giovanni, Madonna and Child with Saint Jerome, Saint Catherine of Alexandria and angels

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna with Child

.jpg)

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance

Pieter de Hooch, The Bedroom

One of the best de Hoochs I’ve ever seen. This reproduction really doesn’t capture the magic of the tiles and the uneven floor.

#notebook #medianotes

This is Alan Kay’s paper on the DynaBook. A transcription of the paper is here.

He quotes Pavese: “To know the world one must construct it.” This is an elegant summary of the paper’s views on how children understand the world through models.

‘We feel that a child is a “verb” rather than a “noun”, an actor rather than an object; he is not a scaled-up pigeon or rat; he is trying to acquire a model of his surrounding environment in order to deal with it; his theories are “practical” notions of how to get from idea A to idea B rather than “consistent” branches of formal logic, etc.`

I love this story of children using the DynaBook to create a microworld. It is both exciting and dangerously seductive.

`Zap! With a beautiful flash and appropriate noise, Jimmy’s spaceship disintegrated; Beth had won Spacewar again. The nine-year-olds were lying on the grass of a park near their home, their DynaBooks hooked together to allow each of them a viewscreen into the space world where Beth’s ship was now floating triumphantly alone.

’“Y’ wanna play again?” asked Jimmy.

’“Naw,” said Beth, “It’s too easy.”

’“Well, in real space you’d be in orbit around the sun. Betcha couldn’t win then!”

`“Oh yeah?” Beth was piqued into action. “How could we do the sun?”

’“Well, uh, let’s see. When the ship’s in space without a sun, it just keeps going 'cause there’s nothing to stop it. Whenever we push the thrust button, your program adds speed in the direction the ship is pointing.”

’“Yeah. That’s why you have to turn the ship and thrust back to get it to ship.” She illustrated by maneuvering with a few practiced button pushes on her DynaBook. “But the sun makes things fall into it…it’s not the same.”

’“But look, Beth,” Jimmy aimed her ship, “when you hold the thrust button down, it starts going faster and faster, just like Mr. Jacobson said rocks and things do in gravity.”

’“Oh yeah. It’s just like the rock had a jet on it pointed towards the earth. Hey, what about also adding speed to the ship that way?”

’“Whaddya mean?” Jimmy was confused.

’“Here look.” Her fingers started to fly on the DynaBook’s keyboard, altering the program she had written several weeks before after she and the rest of her school group had “accidently” been exposed to Spacewar by Mr. Jacobson. “You just act as though the ship is pointed towards the sun and add speed!” As she spoke her ship started to fall, but not towards the son. “Oh no! It’s going all over the place!”

'Jimmy saw what was wrong. “You need to add speed in the direction of the sun no matter where your ship is.”

’“But how do we do that? Cripes!”

’“Let’s go and ask Mr. Jacobson!” They picked up their DynaBooks and raced across the grass to their teacher who was helping other members of their group to find out what they wanted to know.

'Mr. Jacobson’s eyes twinkled at their impatience to know things. They were still as eager as two-year-olds. He and other like him would do their best to sustain the curiosity and desire to crate that are the birthright of every human being.

'From what Beth and Jimmy blurted at him, he was able to see that the kids had rediscovered an important idea intuitively and needed only a hint in order to add the sun to their private cosmos. He was enthusiastic, but a bit noncommittal:

’“That’s great! I bet you the Library has just about what you need.” At that, Jimmy connected his DynaBook to the class’s LIBLINK and became heir to the thought and knowledge of ages past, all perusable through the screen of his DB. It was like taking an endless voyage through a space that knew no bounds. As always he had a little trouble remembering what his original purpose was. Each time he came to something interesting, he caused a copy to be send into his DynaBook, so he could look at it later. Finally, Beth poked him in the ribs, and he started looking more seriously for what they needed. He composed a simple filter for his DynaBook to aid their search…

'Beth discovered that her problem was ridiculously easy if the sun was placed at “zero”, and she simply subtracted a little bit from the “horizontal” and “vertical” speeds of her craft according to where the ship was located. All of the drawing and aninations she and the other kids had done previously were accociplished by using relative notions which coincided with the scope of their abilities at the time. She was now ready to hold several independent ideas in her mind. The intuitive feeling for linear and nonlinear notion that the children gained would be an asset for later understanding of some of the great generalizations of science.

'After getting her spaceship to perform, she found Jimmy, hooked to his DynaBook, and then soundly trounced him until she became bored. While he went off to find a less formidable foe, she retrieved a poem she had been writing on her DynaBook and edited a few lines to improve it…’

What made Jimmy think of adding the sun? Also, its very handy that the sun was a viable project for them to implement. What if Jimmy had thought of making the game 3D? What makes for a microworld that is a fertile place for children to have ideas for things to try? What makes for a microworld that is simple enough for children to implement?

What is Mr Jacobsen’s role? He doesn’t seem to be a question answerer. He seems more of a “teach a man to fish” man. He also doesn’t pepper Beth and Jimmy with questions so he can understand what they are confused about. This reminded me of John Holt’s idea in Why Children Fail that a teacher’s attempts to grasp a student’s level of understanding get in the way of the student reflecting on their own understanding.

How did Beth discover the idea of placing the sun at “zero”?

'A tool is something that aids manipulation of a medium and man is cliched as the “tool building animal”. The computer is also regarded as a tool by many. Clearly, though, the book is much more than a tool, and man is much more than a tool builder…he is an inventor of universes. From the moment he learns to see and to use language, each new universe serves as a medium. (and constraint) of expression in which imagined structures can be embedded, usually with the aid. of tools.’

Must read more about Piaget, Bruner, Hunt, Kagan and Montessori.

’[Moore, the inventor of the talking typewriter] feels that it is not so much that children lack a long attention span, but that they have difficulty remaining in the sane with respect to an idea or activity. The role of “patient listener” to an idea can quickly lead to boredom and lack of attention, unless other roles can also be assumed such as “active agent”, “judge” or “game player”, etc. An environment which allows many perspectives to be taken is very much in tune with the differentiating, abstracting and integrative activities of the child.’

'Where some people measure progress in answers-righttest or tests-passedyear, we are more interested in “Sistine-Chapel-Ceilings/Lifetime.’

’"Sistine-Chapel-Ceilings are not gotten without healthy application of both dreaming and great skill at painting those dreams. As bystander L. d.Vinci remarked, "Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art”. Papert has pointed out that people will willingly and joyfully spend thousands of hours in order to perfect a sport (such as skiing) that they are involved in. Obviously school and learning have not been made interesting to children, nor has a way made to get immediate enjoyment from practicing intellectual skills generally appeared.

'With Dewey, Piaget and Papert, we believe that children “learn by doing” and that much of the alienation in modern education coms from the great philosophical distance between the kinds of things children can “do” and much of 20-cerntury adult behavior.’

'If we want children to learn any particular area, then it is clearly up to us to provide them with something real and enjoyable to “do” on their way to perfection of both the art and the skill. Painting can frustrating, yet practice is fun because a finished picture is a subgoal which can be accomplished without needing total mastery of the subject.

'Playing musical instruments and gaining musical thinking is unfortunately much further removed. Most modern keyboard and orchestral instruments do not provide subgoals which are satisfying to the child or adult for many months, nor do they really give any insight into what music is or how to “do” it on one’s own. IT is usually much more analogous to “drill and skill” in painting a billboard “by the numbers”, and not even getting to use your own numbers or paint!

'The study of arithmetic and mathematics is, in general, an even worse situation. What can a child “do” with multiplication. The usual answer is work problems in the math book! A typical establishment reaction to this is that “Some things just have to be learned by drill”. (Fortunately kids don’t have to learn their native tongue under these circumstances.) Papert’s kids need to use multiplication to make the size of their computer-drawn animations change. They have something to “do” with it.’

'Two of Piaget’s fundamental notions are attractive from a computer scientist’s point of view.

The first is that knowledge, particularly in the young child, is retained as a series of operation models, each of which is somewhat ad hoc and need not be logically consistent with the others. (They are essentially algorithms and strategies rather than logical axioms, predicates and theorems.)

'The second notion is that development proceeds in a sequence of stages (which seems to be independent of cultural environment), each one building on the past, yet showing dramatic differences in the ability to apprehend, generalize and predict casual relations. Although the age at which a stage is attained may vary from child to child, the apparent dependency of a stage on previous stages seem to be invariant. Another point which will be important later on is that language does not seem the mistress of thought but rather the handmaiden, in that there is considerable evidence by Piaget and others that such thinking is nonverbal and iconic.’

#notebook

Context: John Siracusa is notorious for being ruthlessly logical.

Merlin Mann: “It’s just hitting me now that you’re a father to those kids and they have to live up to your standards.”

John Siracusa: “They don’t they just ignore me. They could give two craps what I…”

Merlin Mann, apeing Siracusa: “‘If you can’t define it, how can you defend it?’”

John Siracusa: “The smarter they get, the more their brains develop, the more I gain power over them, because my biggest tool is reason and logic.”

From Children’s Shoes, the latest episode of Reconcilable Differences.

#notebook

Architect Christopher Alexander: “In my life as an architect, I find that the single thing which inhibits young professionals, new students most severely, is their acceptance of standards that are too low. If I ask a student whether her design is as good as Chartres, she often smiles tolerantly at me as if to say, “Of course not, that isn’t what I am trying to do… . I could never do that.”

Then, I express my disagreement, and tell her: “That standard must be our standard. If you are going to be a builder, no other standard is worthwhile. That is what I expect of myself in my own buildings, and it is what I expect of my students.” Gradually, I show the students that they have a right to ask this of themselves, and must ask this of themselves. Once that level of standard is in their minds, they will be able to figure out, for themselves, how to do better, how to make something that is as profound as that.

Two things emanate from this changed standard. First, the work becomes more fun. It is deeper, it never gets tiresome or boring, because one can never really attain this standard. One’s work becomes a lifelong work, and one keeps trying and trying. So it becomes very fulfilling, to live in the light of a goal like this.

But secondly, it does change what people are trying to do. It takes away from them the everyday, lower-level aspiration that is purely technical in nature, (and which we have come to accept) and replaces it with something deep, which will make a real difference to all of us that inhabit the earth.”

Via Michael Neilsen.

#notebook