Mary Rose Cook's notebook

The public parts of my notebook.

Heat

One of the things I like about Michael Mann is that I don’t understand a lot of his decisions. I don’t mean that I see his choice and its aim and that I disagree. I don’t mean I see his choice and think he has missed his aim. I mean I don’t see the choice he made. For example, I have no idea why the opening shot has a train in it, why there is smoke blowing across the screen, why it is night time, or why the camera is on the railway tracks.

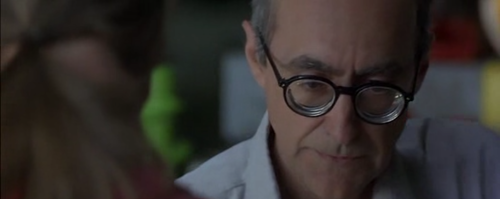

There is something interesting about the way the man adjusts his glasses that feels so real, even though you are unnaturally close to his face.

Note in the background the portentous painting of the girl.

So much of Heat is shot panoramically. Even the little domestic scene where Hanna comes home late and hasn’t called and his wife has been waiting is shot in these great wide vistas. There are yards of space either side of him as he furtively looks up the stairs to see if it is safe to turn on the TV. These yards are used for informative things like the end of the dining table with candle and places for two, and also uninformative things like the great gap between Hanna and the TV and the part of a book shelf.

One could say this decision is about distancing the characters from each other, or showing a home that is mostly empty, or making the street environment spill into Hanna’s home life. Any which way, it makes the Hitchcockian front-on shots all the more arresting. It makes these moments almost the only times when two people actually focus on each other, rather than being drowned in the sea of space between them. Even if that focus or moment of interaction is between a man and the man he is about to kill.

Despite the fact that the men in this shot are moving about all over the place, they are laid out as well as a painting.

It would be trite to call Mann’s landscapes barren or desolate or real, though they are sometimes all these things. I think the overarching feeling is of existence. That there are places like these everywhere, and some of them are the stages for fantastical events like the ones depicted in the film you are watching. They are places where you are alone and, and though nothing is happening at this moment, attention is focused on you.

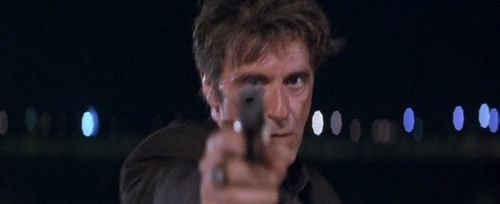

Mann is famous for shots like this:

The cold, blue light appears in Manhunter relatively frequently. But, in his other films, it’s quite rare. Since Collateral, it has almost completely disappeared, replaced by the sodium yellow of street lights that show up on his new, digital cameras. The yellow is far more interesting, because it is a colour we all inhabit. This realism is echoed in the new way he does the sound effects for guns. In Heat and earlier films, the guns made KABLAOWW type sounds that were designed to sound as powerful as possible. From Miami Vice on, the guns made that muffled, low-down-to-the-ground staccato you hear on news coverage of urban wars.

Mann sometimes brazenly disregards authenticity. In the scene at the end of The Last of the Mohicans, when the English girl throws herself off the cliff top after her dead beloved, the light upon the valley is completely different from the light on the characters’ faces when they are talking. In this scene in Heat, the light on Eady’s face makes the whole scene seem unreal, like the thank you letter in Taxi Driver.

Sometimes, shots in Heat seem messy, because there is so much stuff being shown. Cars parked in the street. Books on a table. But it’s all deliberate. Look at how acetic this shot is:

I love this shot so much:

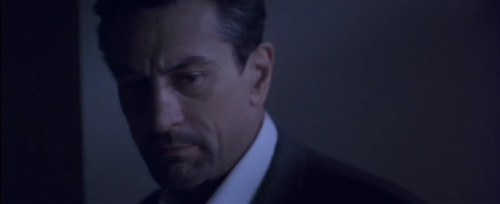

Another straight-on shot showing a tender moment of human connection: McCauley telling Van Zant he is going to kill him.

Another straight-on shot. This time, the background is distant and Hanna is completely alone in the green cold.

The straight-on shots, though often about impending death, are also about recognition. I find great meaning in fact that Hanna and McCauley are the only characters who really understand each other. These two shots are where it begins:

The robbers watching the cops

When McCauley walks into the bank, that click click click music sets the pace for the final part of the film. Though it doesn’t feel like it. Part of the reason the shoot-out is so wonderful is that is happens in what feels like the middle of the film. But this is where an unstoppable series of events happen over a few days that feel like a line of dominoes going over.

I love the change of Val Kilmer’s face when he sees the police.

And the final straight-on shots.

Strangely, not mirrored from Hanna’s perspective.

The final frame. Aeroplanes landing to mirror the trains arriving in the first scene.

#notebook #medianotes